originally published at the Guardian by Katie Allen Friday 24 April

Greece owes money to the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Union following its two bailouts in 2010 and 2012

Greece faces a busy schedule of debt deadlines as well as payments due on salaries and pensions.

Warnings are growing that Greece could crash out of the eurozone as it battles a busy schedule of debt deadlines as well as payments due on salaries and pensions.

Photograph: ALKIS KONSTANTINIDIS/REUTERS

Crunch talks between Greece and its eurozone creditors are under way, but investors are growing increasingly sceptical that the country can reach an agreement on reforms and unlock the aid it needs from international lenders to avoid a debt default.

Greece owes money to the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Union following its two bailouts in 2010 and 2012. Athens is waiting for a further €7.2bn (£5.2bn) in rescue funds and without that money it is unlikely the country can pay almost €1bn due to the IMF in early May. Fears are growing that Greece will therefore default, precipitating the country’s exit from the eurozone.

Here we look at the near-term debt deadlines for Greece and what money it has left to meet them. We also consider how quickly funds have been flowing out of Greek banks.

The current disagreements with our partners are not unbridgeable – we should map out a forward-looking plan for Greece that avoids the ‘austerity trap’ and the ‘reform trap’

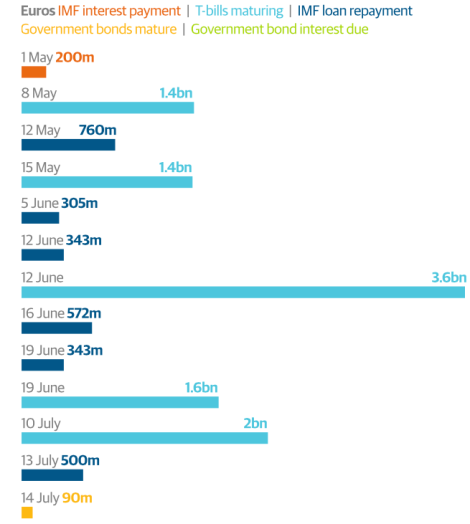

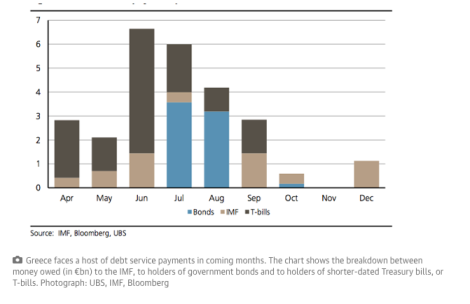

This covers repayments and the largest interest payments on debt due from Greece in coming months. The list includes Treasury bills, usually called T-bills for short, which are shorter-dated government bonds sold to domestic investors, such as Greek banks, and to a smaller extent to foreign investors. Greece has previously managed to convince bondholders to roll over their T-bill holdings, but with the country’s position growing more uncertain this pattern will become harder to maintain.

What is left?

On top of debt repayments and interest payments, Greece has to cover the usual costs of pensions and salaries for the public sector. Salary and pension payments due in late April are thought to come to around €1.7bn.

There have been warnings that Greece faces a choice between meeting those commitments and its debt servicing – and that it cannot afford both unless the next lot of bailout funds is paid out.

Unnamed finance ministry officials in Greece have tolds Reuters news service that Greece will need to tap all the remaining cash reserves across its public sector, a total of €2bn, to pay wages and pensions at the end of the month. But at the same time, and without providing any figures, Greece’s finance ministry denied in a statement that it would need to tap remaining cash reserves to meet salary payments.

Economists say some scepticism should apply to any claims the coffers are almost empty.

Paolo Pizzoli , senior economist at ING in Milan comments:

The Greek government has tried to squeeze money out of a variety of sources for a couple of months now.

Capital expenditure has reportedly been trimmed, state payments to third parties have been postponed and reserve funds of public institutions tapped, but with scarce chances to get the relevant data evidence.

Furthermore, the ‘running out of funds’ rhetoric has often been used instrumentally to affect negotiations by parties involved, adding to the noise.

Bottom line, we, or at least I, don’t now how much money the country has now available, but I suspect that there is not much left in the coffers.

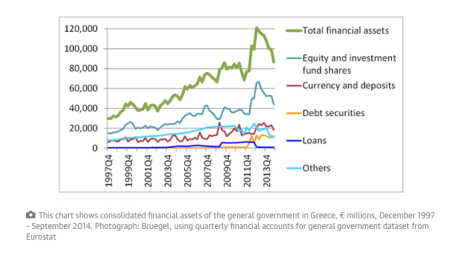

Zsolt Darvas at the thinktank Bruegel also urges caution about any warnings that Greece is about to run out of cash. He notes that Greece has financial assets it can fall back on. The most up-to-date data, from September 2014, showed the Greek government had assets worth €86.6bn. Darvas adds:

Even if the €86.6bn has declined by a dozen or two, and even if not all of the remaining assets could be easily used to pay for obligations, there is still a lot, and much more than the €30bn assets the Greek general government had at the end of 1997 (see chart below).”

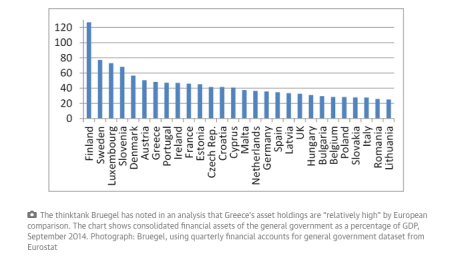

Darvas at Bruegel also notes asset holdings in Greece are “relatively high” by comparison with other European countries. As a share of financial assets in GDP, Greece ranked seventh among the 28 EU countries in September 2014, as shown here:

What is happening at Greek banks?

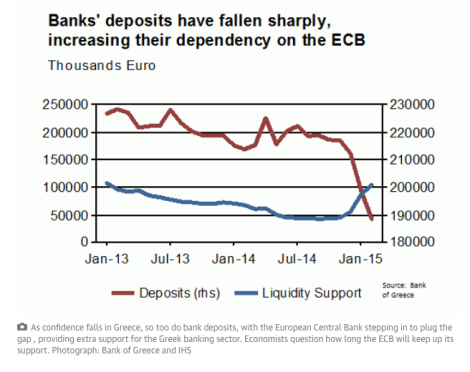

Growing uncertainty about Greece’s position in the eurozone and fears of rising political instability have prompted savers to take their money out of Greek banks and instead keep it at home or move it overseas.

Banks suffered deposit outflows of some €25bn between December and February, according to the latest figures. The capital flight continued in March but the pace slowed somewhat with net withdrawals at €3bn, according to a report by news service Bloomberg.

Gabriel Sterne at the consultancy Oxford Economics comments:

The big surprise, if anything, is it still remains more of a bank jog than a bank run. It wouldn’t take much, however, for confidence to go and the run to accelerate.”

Given deposits are the basic source of funding for banks, their depletion is seen representing a significant risk for the Greek financial system. So far, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been prepeared to step in and fill the funding gap for Greek banks by increasing the cap on emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). However, as the name the implies, this was never intended to be a long-term measure to keep a eurozone country afloat.

Sterne warns that capital controls, whereby limits are placed on what savers can withdraw from banks, could be around the corner for Greece:

One more turn of the financial screw and Greece would be in capital controls; a terrible symptom of political failure of a six-year attempt to restore sustainability.”

Diego Iscaro, senior economist, at the consultancy IHS says the ECB’s role is crucial. He believes the risk of Greece leaving the eurozone is “increasing by the day”. Iscaro adds:

The key will be held by the position taken by the ECB: a withdrawal of its support to the Greek banking sector resulting from a sovereign default could be the trigger that decides Greece’s fate in the eurozone.”

Reblogged this on iGlinavos.

Reblogged this on iGlinavos.

A Greek comedian, with serious information said in a humorous way gives a different viewpoint.

The wealth of Germany today is because of the money taken by the Nazis to fund their occupation of Greece and their war in North Africa, during the second world war.

It is Germay that owes all the debt of Greece to the EU.